[Below Cecily Garber, a grad student affiliate in English and recipient of a Unit for Criticism travel grant last fall, writes about the representation of class politics in Downton Abbey.]

Upstairs, Downton?

Written by Cecily Garber (English)

While I am as much a fan of Downton Abbey as any other lover of costume drama laced with intrigue and social commentary, a brief dip into the 1970s British series Upstairs, Downstairs, from which Downton clearly takes many cues, has made me think twice about how much social commentary Downton really has, particularly on economic disparity and class differences. Granted, I have only seen the first season of both Downton and Upstairs, Downstairs, but that is enough for me to know that many strands of Downton’s plot are inspired by Upstairs, Downstairs (e.g., both feature gay footmen involved with aristocratic houseguests, daughters with radical political ideas at odds with family heritage, and butlers with an unshakeable sense of dignity and propriety who run the house impeccably). But more interesting than superficial similarities are the ways that parallel strands of Downton and Upstairs, Downstairs play out differently, revealing different attitudes toward the master-servant relationships that are at the heart of both series.

Downton’s first episode features a stranger’s arrival at the estate, a convention that promises to initiate the audience into the customs of the great house by showing how the stranger, in this case the new valet Bates, adjusts to a new way of life. But Bates does not ask the kind of questions that an audience unfamiliar with Downton’s well-oiled system of service would ask. Rather, he appears to be immediately at home and, in fact, relieved to have arrived in this new world. Upon seeing his small and spare room in the attic, containing a twin bed, small dresser, and nightstand all washed cream white, he says, “Oh, yes, I shall be very comfortable here.” Bates is an outsider at Downton, but mostly because he is lame, not because he finds its habits objectionable or unusual. When learning his new duties from the footman, Bates opens a case of snuffboxes, which the master collects; “Strange,” he says, “how we live with this pirate’s hoard within our reach, yet none of it’s ours.” When he does finally remark on the strangeness of master-servant relationships, he doesn’t criticize it and uses the pronoun “we” when voicing this thought; already on his first full day, Bates identifies himself with his fellow servants and his place at Downton so much that he can articulate its inequities as an unquestionable commonplace.

Upstairs, Downstairs opens with the arrival of a stranger too, but one that is a much ruder awakening. The young Clémence is to be the new under housemaid, and she presents herself by knocking on the front door of 165 Eaton Place in central London, the setting of the show. She is shooed to the basement door (unlike Bates who knows to go there and is first seen inside the house below ground). Upon entering the house, she is re-clothed and re-named and thrust into a world that looks unfair and illogical to her. “Clémence” is thought not to be a servant’s name, so she is quickly rechristened the simpler “Sarah.” Sarah questions the butler's authority, asking, “What makes you my better, I just want to know?”

Over subsequent episodes Sarah continues to question the way things are done, pushing the audience to question the system of service too. When she wakes up, she complains about the cold room and floor and the ill fit of the second-hand uniform she has to wear. In Downton the servants’ rooms generally look quite pleasant, washed with light and marked with a shabby chic grace, whereas in Upstairs, Downstairs the rooms are much darker. Sarah complains repeatedly about being stuffed in the attic at night and relegated to the basement for much of the day. She ends up leaving, not because she has an injury like Bates, but of her own volition because she has great imagination and an irrepressible personality, and she wants to see more of the world.

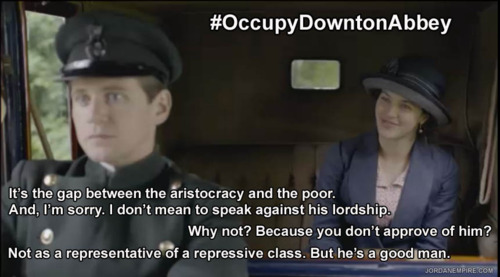

In Downton, it is the unlikeable characters who lack integrity--for example, the lady’s maid O’Brien and the footman Thomas--who most often express strong discontent with their place and bring to light the cold facts of the servant-master relationship. Characters like Branson the chauffer, who question the system from sounder moral grounds, are marginal compared to Sarah. Upstairs, Downstairs thoroughly questions rules that the good servants in Downton quietly accept. I won’t give away the punch line of a pivotal episode of Upstairs, Downstairs’ first season, "I Dies of Love," in case any reader cares to it dig up, but I will say that it makes a mockery of the masters’ “benevolence,” their efforts to improve their servants’ lives; it clearly underscores the dark consequences of the stark differences between opportunities open to different classes.

In light of the growing income disparity in this country and elsewhere, it seems that the forty-year old series Upstairs, Downstairs, at least its first season, is more critically engaged in social debates than the infectious but hagiographic Downton Abbey. Considering the turbulent political atmosphere of 1971, the year of Upstairs, Downstairs’ first season, the earlier show’s more radical outlook may come as no surprise; at a time when “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland were nearly at their peak and debates about immigration to Britain were stormy too, class politics might have seemed relatively tame and well-trod. But then as now unemployment was exceptionally high—in 1971 it reached a post-WWII peak in the U.K.—which is perhaps one reason the unlikely show became so popular (the first season did not air until almost a year after it had been shot, and then at the unpromising time of 10 PM on Sunday evenings, yet went on to run for four more seasons, and ended to its producers’ great dismay only by its creators’ firm decision to do so). Period drama fans today, like their counterparts in 1971, might well appreciate less glorification and more defamiliarization of class differences that speak to disparity experienced in their own lives.