[This first of two final entries in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, was posted prior to the publication of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s (Duke University Press), is co-written by Lauren Goodlad and Rob Rushing, The second entry, a follow-up from Lilya Kaganovsky, appears next.]

[This first of two final entries in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, was posted prior to the publication of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s (Duke University Press), is co-written by Lauren Goodlad and Rob Rushing, The second entry, a follow-up from Lilya Kaganovsky, appears next.]"GROUNDHOG DAY"

Written by Lauren M. E. Goodlad (Unit for Criticism/English) and Robert A. Rushing (Unit for Criticism/Italian/Comparative Literature)

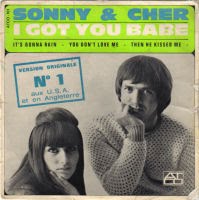

In the 1993 movieGroundhog Day, Bill Murray plays Phil Connors, a narcissistic weatherman with an itch for his producer Rita, played by the fetching Andie McDowell. In the words of Wikipedia, “during a hated assignment covering the annual Groundhog Day,” Connors “finds himself repeating the same day over and over again. After indulging in hedonism and numerous suicide attempts, he begins to reexamine his life and priorities.” In the end, a wholly reformed Connors wins Rita’s love, breaking the cycle of repetition. Fans of the film will remember that Connors’ entrapment in the events of a single day, with his own moral agency the only variable that changes, is signaled by an alarm clock on his nightstand waking him each morning to the same tune: “I Got You Babe,” the 1965 pop hit by Sonny and Cher. When the new-model Connors wakes up to find Rita beside him, he knows that Tomorrowland has finally come.

In the 1993 movieGroundhog Day, Bill Murray plays Phil Connors, a narcissistic weatherman with an itch for his producer Rita, played by the fetching Andie McDowell. In the words of Wikipedia, “during a hated assignment covering the annual Groundhog Day,” Connors “finds himself repeating the same day over and over again. After indulging in hedonism and numerous suicide attempts, he begins to reexamine his life and priorities.” In the end, a wholly reformed Connors wins Rita’s love, breaking the cycle of repetition. Fans of the film will remember that Connors’ entrapment in the events of a single day, with his own moral agency the only variable that changes, is signaled by an alarm clock on his nightstand waking him each morning to the same tune: “I Got You Babe,” the 1965 pop hit by Sonny and Cher. When the new-model Connors wakes up to find Rita beside him, he knows that Tomorrowland has finally come.And Don Draper?

Season 4 of Mad Men vividly poses the question of whether Don can make the kind of change which made Groundhog Day “a tale of self-improvement” which emphasizes “that the only satisfaction in life comes from turning outward and concerning oneself with others rather than concentrating solely on one's own wants and desires.” When we first find Don in the season premiere (“Public Relations”), he is so devastated by the ruin of his marriage and family that he has temporarily lost his mojo—his inspired knack for selling.

The art of selling (and the practice of salesmanship as art) has always been the core of Don’s character, whether he is selling fur coats, Lucky Strikes, and the Kodak carousel, or—that most crucial of all commodities—Donald F. Draper. Season 4 sees Don descend into alcoholism, a sad caricature of his former self, before finally steadying himself through the symbolism of journal-writing and swimming (4.8, “The Summer Man”). The episode is remarkable for its introduction of voice-over, enabling Don to narrate parts of his story like a latter-day Jane Eyre. When he passes the chance to bed Faye Miller on their first date, telling her “That’s as far as I can go right now,” he signals the potential for a new kind of Don: Reader, I am different now.

But, while Mad Men has always been a neo-realist narrative (adapting the forms of nineteenth-century serial fiction to television), it has never been a classic Bildungsroman in which the narrative arc coincides with the protagonist’s moral growth. Indeed, Don’s morality has always been the subject of debate since he is both an anti-hero (the “handsome two-bit gangster” Faye describes in “The Summer Man”), and a character with an almost Nietzschean potential to creatively transcend his hollow milieu. The show’s genius is to convince us that while Don is a fraud by every measure we can imagine—a liar, a seducer, even a coward at times—he is also better than the world that made him. We must believe in Don’s nobler instincts and thrill to his moments of transcendence even while knowing that if he ever sustained them, he would no longer be Don—and we would no longer be watching Mad Men.

Marriage to Faye would mean a Don who has outgrown the fantasy of replacing the mother he never knew—quite literally a whore—with the “beautiful and kind” “angel” he describes to Betty after he torpedoes her modeling career in Season 1 (Episode 8 “Shoot”). It is a fantasy of wedlock that creates the need for a fantasy of escape as Don repeatedly splits himself between the man who provides for the angel in his house, and the man who craves stronger femininities like those of the bohemian Midge, the professional Rachel, and the ballsy Bobbie Barrett.

Marriage to Faye would mean a Don who has outgrown the fantasy of replacing the mother he never knew—quite literally a whore—with the “beautiful and kind” “angel” he describes to Betty after he torpedoes her modeling career in Season 1 (Episode 8 “Shoot”). It is a fantasy of wedlock that creates the need for a fantasy of escape as Don repeatedly splits himself between the man who provides for the angel in his house, and the man who craves stronger femininities like those of the bohemian Midge, the professional Rachel, and the ballsy Bobbie Barrett.One of the most moral characters ever depicted on Mad Men, Season 4’s Dr. Miller holds out the prospect of monogamous romance—Ah, love let us be true to one another!—along with a turn from the gendered separation of spheres which doomed the Draper marriage, as it does most unions that find a man telling his wife, “It’s my job to give you what you want” (“Shoot”). Miller’s professional gift is to know what people desire even before they know it themselves (she is the first person to cast Don as a “type,” and predicts that he will remarry within a year). If on one level this makes her just another player, her efforts to separate the intimacies of private life from the instrumental relations of a “stupid office” strike us as sincere.

The conflation of love and work has come up before in Caroline Levine’s post on Episode 11 (“Chinese Wall”), and it reaches a kind of apotheosis when Don diverges from the path of health, openness, and growth which Faye has represented throughout this season. In “Tomorrowland” Ken Cosgrove becomes the surprising exemplar of a principled refusal to use his father-in-law to win a new client: “I’m not Pete,” he insists, adding that his wife “Cynthia is my life, my actual life.” Later, Ken and Peggy express the distinction between work and love with their gleeful but unerotic embrace when they land a new account.

Don’s engagement to his secretary Megan, is explicitly marked as repetitious first by Roger Sterling (“See, Don? This is the way to behave,” Roger says, implicitly referring to his own marriage to a young secretary), and later by Joan (“It happens all the time” and “he’s smiling like a fool, like he’s the first man who ever married his secretary”). Ironically and recursively, in last year’s third episode (“My Old Kentucky Home”) it was Don who was calling Roger a fool.

Don’s engagement to his secretary Megan, is explicitly marked as repetitious first by Roger Sterling (“See, Don? This is the way to behave,” Roger says, implicitly referring to his own marriage to a young secretary), and later by Joan (“It happens all the time” and “he’s smiling like a fool, like he’s the first man who ever married his secretary”). Ironically and recursively, in last year’s third episode (“My Old Kentucky Home”) it was Don who was calling Roger a fool.Don’s following in Roger’s footsteps has been a recurring theme throughout the season. It is the central narrative twist of the sixth episode, “Waldorf Stories” (in which Don’s hiring of Danny Siegel after drinking too much parallels Roger’s hiring of the young Don). And it persists in Don’s taking to journal-writing while Roger composes his risible memoir, Sterling’s Gold. Most poignant of all, when Don first climbs on top of Megan in “Chinese Wall,” the camera cuts to the loveless Sterling home—anticipating the tomorrow that Season 5 may yield.

Though Don—as ever gaga in California—may believe that his impromptu proposal is heaven-sent by Anna Draper, it seems all too clear that Megan is not the “right woman,” like Rita in Groundhog Day, who can liberate him from the cycle of repetition. Indeed, every episode of Mad Men begins with precisely this narrative: in the iconic credit sequence the world dissolves and collapses, and Don falls, only to find himself miraculously reconstituted with a cigarette in one hand and—one assumes—a drink in the other. Like his son Bobby who wants to visit Tomorrowland (a Disney exhibit that opened in July 1955), Don does not seek the tomorrows of what Ken calls “actual life.” He seeks the fantastic, non-existent tomorrows conjured up by theme park planners and ad execs like himself. As always with Mad Men’s depiction of California as magic kingdom, Tomorrowland is not a realistic future, with all of its promise and menace, but an infantile withdrawal from the present.

Whereas the season ends with Betty ready to admit that the future augured in last year’s haunting "Shahdaroba" sequence has not turned out to be “perfect,” it leaves Don, who “only likes the beginnings of things” at the very crest of fantasmatic bliss. More keen to sell himself on marriage than to sell to clients, Don upstages Peggy’s professional coup with the kind of engagement he once called “foolish.” In the brilliant seventh episode, “The Suitcase,” Don and Peggy sealed their platonic bond and mutual dedication to work over an ad for Samsonite. But Don now believes that he can have it all. The secretary who caught his eye at the end of “Hands and Knees” and craftily seduced him in “Chinese Walls,” is now not only Maria von Trapp (a better version of Betty’s maternal angel), but also Peggy to boot (she has “the same spark as you,” Don tells his incredulous protegé).

Whereas the season ends with Betty ready to admit that the future augured in last year’s haunting "Shahdaroba" sequence has not turned out to be “perfect,” it leaves Don, who “only likes the beginnings of things” at the very crest of fantasmatic bliss. More keen to sell himself on marriage than to sell to clients, Don upstages Peggy’s professional coup with the kind of engagement he once called “foolish.” In the brilliant seventh episode, “The Suitcase,” Don and Peggy sealed their platonic bond and mutual dedication to work over an ad for Samsonite. But Don now believes that he can have it all. The secretary who caught his eye at the end of “Hands and Knees” and craftily seduced him in “Chinese Walls,” is now not only Maria von Trapp (a better version of Betty’s maternal angel), but also Peggy to boot (she has “the same spark as you,” Don tells his incredulous protegé).On some level, of course, Don understands that Tomorrowland is an illusion, but without ever being consciously aware of it. Early in the episode, he makes his pitch to the American Cancer Society, and they ask him why he boldly (and unilaterally!) withdrew the firm from cigarette advertising. He tells them, “I knew what I needed to do to move forward.” But in fact Don knows exactly how to not move forward, both personally and professionally, precisely because this is what advertisers understand best. Advertising, we have been told repeatedly this season, is what negotiates between our desire and our conscience, allowing us to gratify ourselves and salve our consciences at the same time. It mediates, as Faye says, what people want to do, and what they think they ought to do.

Hence, cigarette advertisers know just how to snare a teenage market, though Don’s explanation applies at least as much to himself as it does to teenage smokers: cigarette advertisers offer “a two-pronged attack, promising adulthood and rebellion. But teenagers are sentimental as well.” He suggests a campaign showing children and parents together, while making it clear that the parents—thanks to their smoking—are “not long for this world.” The chairwoman objects: “But [teenagers] hate their parents!” She has realized that an appeal to the future, to avoiding a tomorrow without parents, is fruitless—it’s all conscience, without the gratifying desire. Don reassures her: “They won’t be thinking about their parents. They’ll be thinking about themselves—that’s what they do. They’re mourning for their childhood, more than they’re anticipating their future.”

In other words, we can sell people self-pity and narcissistic self-interest under the guise of altruistic love. That’s a product Don himself—just like his cigarette habit—can’t give up. The “tomorrow” that Don wants to sell to potential smokers is a fantasy, not in the sense that it doesn’t exist, but precisely in the Disney sense: a gratifying playground of self-interest and escapism. In this way Don’s New York Times gambit in last week’s “Blowing Smoke,” is not so much deconstruction as reconstruction of the show’s famous pilot, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.”

Don's teenage rube is, of course, Don himself, even if he doesn’t recognize it. And this lack of recognition may be why he is doomed to repeat, like Phil Connors, an endless cycle of “hedonism” and, figuratively at least, “suicide attempts.” Mad Men has always used its advertising campaigns as a way of speaking about larger thematic concerns, as well as a way of talking about what’s happening inside its characters. At its very best, the show portrayed Don as simultaneously completely manipulative and completely sincere, talking about himself and the product, but also –in a more self-referential vein—about the viewer and the show, all at once.

But lately, Mad Men has reached beyond the realism that made its early seasons so novelistic. This may be inevitable for a show so wholly cathected to a narrative of secret identity which has already been thrice revealed (by Pete in Season 1; by Anna, retrospectively, in Season 2; and in the kind of denouement that makes the serial form so engrossing, by Betty in the last season). By now Don’s secret has exhausted itself and Season 4 has found the show’s inventive writers experimenting with different forms. The Mad Men of this season is more formally eclectic, more melodramatic (the panic attack that leads to Don’s confession), and more self-referential (the playful feint in last week’s episode which makes us think Don is returning to journal writing when he is pulling off the kind of stunt which worked in “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword”). Yet, for all its experiments, the season has not been more attentive to people of color: one hopes that the regrettable departure of Carla may find next year’s season including the show’s first principal African-American character.

But lately, Mad Men has reached beyond the realism that made its early seasons so novelistic. This may be inevitable for a show so wholly cathected to a narrative of secret identity which has already been thrice revealed (by Pete in Season 1; by Anna, retrospectively, in Season 2; and in the kind of denouement that makes the serial form so engrossing, by Betty in the last season). By now Don’s secret has exhausted itself and Season 4 has found the show’s inventive writers experimenting with different forms. The Mad Men of this season is more formally eclectic, more melodramatic (the panic attack that leads to Don’s confession), and more self-referential (the playful feint in last week’s episode which makes us think Don is returning to journal writing when he is pulling off the kind of stunt which worked in “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword”). Yet, for all its experiments, the season has not been more attentive to people of color: one hopes that the regrettable departure of Carla may find next year’s season including the show’s first principal African-American character. Season 4 has also seen the show’s foray into meta-textual references (as Sandy Camargo noticed about the allusion to Mad Men’s own Emmy nominations in “Waldorf Stories.”) This is the same kind of reference that we find in the music chosen for the credit sequence of this season’s finale. As Don lies in bed, turning uneasily to look at his nightstand, the tune we hear, of course, is “I Got You Babe.” To be sure, the song is just the sort of kitschy sentimentalism that expresses what we think about Don’s marriage, and, though he is not young, impoverished, or long-haired, it is from 1965. But, like Don’s telling glance at the nightstand, the song surely points to Phil Connors’ “wake-up call,” both literal and metaphoric, in Groundhog Day.

Season 4 has also seen the show’s foray into meta-textual references (as Sandy Camargo noticed about the allusion to Mad Men’s own Emmy nominations in “Waldorf Stories.”) This is the same kind of reference that we find in the music chosen for the credit sequence of this season’s finale. As Don lies in bed, turning uneasily to look at his nightstand, the tune we hear, of course, is “I Got You Babe.” To be sure, the song is just the sort of kitschy sentimentalism that expresses what we think about Don’s marriage, and, though he is not young, impoverished, or long-haired, it is from 1965. But, like Don’s telling glance at the nightstand, the song surely points to Phil Connors’ “wake-up call,” both literal and metaphoric, in Groundhog Day.Don will have to repeat this story, evidently, unless and until he finally gets it right.