[The third in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 6 of AMC's Mad Men, posted in collaboration with the publication ofMADMEN, MADWORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, andthe 1960s(Duke University Press, March 2013) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

"Out in the Open"

Written by: Robert A. Rushing (Italian/Comparative Literature)

|

| Joe Namath card from 1968 |

“To Have and to Hold” opens with a three-shot: Don, Pete and Timmy from Heinz ketchup, discussing the possibility of an “exploratory mission” to see if SCDP can capture the lucrative and prestigious condiment account, in addition to (or in place of) the Heinz baked beans account they already have. They agree to give it a shot, and Timmy stands up to leave, noting that he has a rendezvous with a lady in a few minutes. In a rapid, much-practiced and rather repulsive gesture, Timmy licks his wedding ring and then slides it off into his pocket, pointedly noting that he doesn’t “need much of an excuse to come to Manhattan.” Don smiles his forced business smile in response, and a minute later, Pete offers his own rather sad apartment to Don, should the need arise to “spend the night in the city.” Don, as is so often the case when dealing with Pete, marvels at Pete’s tactlessness and foolishness. “I live here,” Don he reminds him.

“To Have and to Hold” opens with a three-shot: Don, Pete and Timmy from Heinz ketchup, discussing the possibility of an “exploratory mission” to see if SCDP can capture the lucrative and prestigious condiment account, in addition to (or in place of) the Heinz baked beans account they already have. They agree to give it a shot, and Timmy stands up to leave, noting that he has a rendezvous with a lady in a few minutes. In a rapid, much-practiced and rather repulsive gesture, Timmy licks his wedding ring and then slides it off into his pocket, pointedly noting that he doesn’t “need much of an excuse to come to Manhattan.” Don smiles his forced business smile in response, and a minute later, Pete offers his own rather sad apartment to Don, should the need arise to “spend the night in the city.” Don, as is so often the case when dealing with Pete, marvels at Pete’s tactlessness and foolishness. “I live here,” Don he reminds him.This sequence, as is the case with most of the episode, traces out the consequences of prior episodes: SCDP’s inevitable betrayal of Raymond (of Heinz baked beans), Peggy’s inevitable betrayal of Stan (who let her know about the ketchup possibility in one of their many telephonic exchanges of confidences), Pete’s inevitable betrayal of Don by failing to keep the ketchup account a secret… Most particularly, however, this opening reminds us of marital betrayal (“to have and to hold…”). Don chastises Pete for the same reason Trudy did in last week’s episode (“The Collaborators”)—for failing to understand the need to keep the wife in one location (to hold), and the mistress in a separate and distant location (to have). Of course, there is plenty of dramatic irony for the viewer here—Don’s betrayal of his own wife is happening even closer to home than Pete’s.

This trio of cheating husbands does have one member who knows how it’s done, however, the repulsively suave and confident (“I have that power”) Timmy. Here we have to return to that gross and curiously excessive gesture of the removal of the wedding ring using the tongue for lubrication, a gesture that takes perhaps two seconds of screen time and that elicits no comment or visible reaction from either Pete or Don. It is part and parcel of a quiet but enormous sea change visible throughout this episode: sex has changed. If before sex was desirable, important, secretive and dangerous, it emerges in this episode in its proto-1970s form: something open, banal, public and vulgar. Nowhere is this more visible, of course, than when two of Megan’s colleagues (Mel and Arlene) attempt to “swing” with Don and Megan (it is clear that this is not partner swapping, and that there is at least as much interest in same-sex coupling as in hetero). The whole scene begins when Megan attempts to allay Don’s worries about her upcoming love scene on the show. “When we, you know, do things on the show, it’s all very tasteful,” she claims, not very convincingly. “Well, it’s not real life,” replies Arlene. This exchange suggests that there’s a question about style in the episode; what is at stake is not so much the thing itself, but how it is depicted—and that is what is changing.

This trio of cheating husbands does have one member who knows how it’s done, however, the repulsively suave and confident (“I have that power”) Timmy. Here we have to return to that gross and curiously excessive gesture of the removal of the wedding ring using the tongue for lubrication, a gesture that takes perhaps two seconds of screen time and that elicits no comment or visible reaction from either Pete or Don. It is part and parcel of a quiet but enormous sea change visible throughout this episode: sex has changed. If before sex was desirable, important, secretive and dangerous, it emerges in this episode in its proto-1970s form: something open, banal, public and vulgar. Nowhere is this more visible, of course, than when two of Megan’s colleagues (Mel and Arlene) attempt to “swing” with Don and Megan (it is clear that this is not partner swapping, and that there is at least as much interest in same-sex coupling as in hetero). The whole scene begins when Megan attempts to allay Don’s worries about her upcoming love scene on the show. “When we, you know, do things on the show, it’s all very tasteful,” she claims, not very convincingly. “Well, it’s not real life,” replies Arlene. This exchange suggests that there’s a question about style in the episode; what is at stake is not so much the thing itself, but how it is depicted—and that is what is changing.  This episode, in other words, is chronicling the change from the minimalist and rather highbrow restraint of the 1960s style to the stylistic excesses of the “let it all hang out” 1970s. On some level, it’s tracing out the death of Mad Men, since it was precisely the mid-century modern style that attracted most viewers to the show in the first place. Culture, it seems, is heading downhill. “To Have and to Hold” is actually filled with stylistic demotions: Joan and her friend Kate, for example, pretend to be secretaries, even teenagers, for their night out on the town. The whole experience is awkward and perhaps fun while it’s happening, and rather humiliating in retrospect Arguably, this is a perfect description of the 1970s as a decade. (This sequence seems to be part of the series’ never-ending quest to provide us with spectacles of Joan’s quiet, stoic suffering, although it is nothing compared to Harry Crane’s cruelty later in the episode.)

This episode, in other words, is chronicling the change from the minimalist and rather highbrow restraint of the 1960s style to the stylistic excesses of the “let it all hang out” 1970s. On some level, it’s tracing out the death of Mad Men, since it was precisely the mid-century modern style that attracted most viewers to the show in the first place. Culture, it seems, is heading downhill. “To Have and to Hold” is actually filled with stylistic demotions: Joan and her friend Kate, for example, pretend to be secretaries, even teenagers, for their night out on the town. The whole experience is awkward and perhaps fun while it’s happening, and rather humiliating in retrospect Arguably, this is a perfect description of the 1970s as a decade. (This sequence seems to be part of the series’ never-ending quest to provide us with spectacles of Joan’s quiet, stoic suffering, although it is nothing compared to Harry Crane’s cruelty later in the episode.)  |

| James Garner in Marlowe (1969) |

This movement, from a highbrow and mannered art text (reminiscent of 1960s cinema) to a popular, even vulgar, style (reminiscent of 1970s television) is present at every level of “To Have and to Hold.” Let’s take a look for a moment at that opening sequence again. It begins with a classic Mad Men shot—immaculately careful framing, with the screen divided into three vertical sections (a composition we’ll see again, when Don and Sylvia ride the elevator together). The colors are striking and, as always, carefully chosen—the green and the blue glass panels match the green and blue suits that Don and Timmy are wearing in the same sequence (see my post on color matching in “Potemkinville” [4.2]) in Season 4.

But one can’t help but notice what has changed—the sleek minimalism of two seasons ago has disappeared, replaced by rococo kitsch: the multiple textures of the glass, matched by the multiple and clashing patterns in Timmy’s suit and ascot (plaid and paisley, together again!).

Dawn’s pink, ruffled blouse exactly matches the color and textural qualities of the ceramic roses on her desk—but the sense of visual restraint and minimalism that defined the “Mad Men style” is gone. Indeed, throughout “To Have and to Hold,” the lighting and colors are unusually bright. Mad Men, like most contemporary “quality” television, has generally preferred a cooler color palette and low light, since these looks were considered “cinematic,” while bright lights and garish colors were seen as cheaper looking and televisual.

Nowhere, however, is this shift in codes more apparent than in this episode’s treatment of sound. Mad Men has always made use of standard cinematic codes of sound, such as the “sound bridge.” A sound bridge is when we hear the sound from the next scene while still watching the first scene. For example, as Joan and Kate finish their conversation in Joan’s apartment, we hear a loud elevator bell; then the camera cuts to reveal Don in an elevator. The effect is sophisticated and typical of film, because it assumes that spectators are paying a lot of attention and understand that they are watching something complex, and so won’t be confused. Music on screen is usually divided into two kinds: diegetic (music that the characters on the show can hear, like what’s on the radio) and non-diegetic (music that we can hear and that they can’t, like soundtrack music). Music in Mad Men has been sophisticated and restrained—that is, cinematic. Most music is diegetic, apart from the music played over the closing credits, and soundtrack music is used sparingly (this is typical not just of film, but specifically of art film). In “To Have and to Hold,” however, something quite strange and surreal happens at several points—not just soundtrack music, but specifically “television” music (rather cheesy music at that) begins to play.

The first time we hear it is just after Harry Crane takes a grinning bite of his danish, just before we cut (sound bridge!) to Stan on a “secret mission” (the secret Heinz ketchup account, now only known as “Project K”), carrying a mysterious duffel bag. The music (jazzy, swinging) is typical for a spy show of the period: chromatic piano, vibraphone, strings, all suggesting tension and mystery. It is played for clearly comic effect, coming to a perfectly synchronized end as Stan closes the door marked “PRIVATE” behind him. The baffled Michael Ginsberg turns and addresses the whole room (and by extension, us): “I saw this thing on a spy show…” This address suggests for just a brief moment that Michael has heard the music, too, that it is actually diegetic music—as if the characters in Mad Men were living in a TV show, complete with TV music!

The second time the music appears is just after Harry Crane proposes his “Joe Namath in a straw hat” idea, right before we cut to Joan striding purposefully through the office in pursuit of the truant Scarlett (dressed in a color matching—but now blindingly bright—scarlet dress). It is still jazzy, with horns and vibraphone, more upbeat and suited to light comedy. And thus forms a strangely discordant note, since Joan is about to fire Scarlett, after all. Both times, I found that I was expecting a laugh track to appear as well, so strongly had my “television code” been activated.

This overall movement from a mid-century minimalism (loosely identified with art and with cinema) to a late 1960s, early 1970s televisual aesthetic (bright, vulgar, counter-cultural, excessive) perhaps reaches its audio-visual peak when Joan and her friend Kate find themselves at the Electric Circus, which only a year or two earlier had been run by Andy Warhol. The Velvet Underground had been the house band, featuring multimedia events called the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” (I was sorely tempted to use this as the title for the post), along with avant-garde music of all varieties (indeed, the New Yorker's classical music critic Alex Ross was one of the first to blog on the episode).

We see something like this as Joan sits next to her friend making out with their waiter, patiently sipping her drink. Lights and shadows float on screens as “Bonnie and Clyde” by Serge Gainsbourg (and featuring Brigitte Bardot!) plays in the background (in case you missed the title, the young man who ends up making out with Joan provides it, as a play on their own names, “Johnny and Joan… Bonnie and Clyde”). As Joan—amused, but clearly not really interested—begins to kiss Johnny back, the camera pans up and to the right, half embarrassed to keep watching, and half more interested in the fascinating patterns of colored lights.

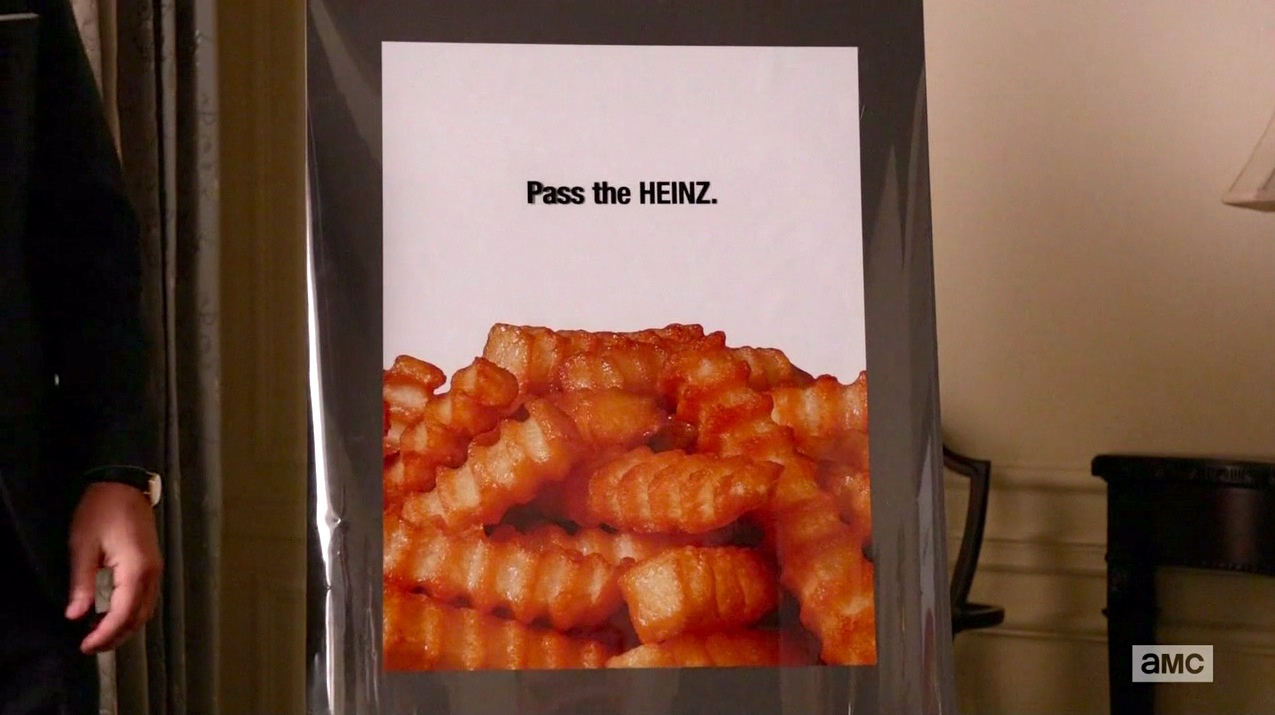

This preference for excess over restraint even appears in the show’s advertising plot. Don continues to try out his minimalist, existential advertising pitches, hidden behind locked doors in tinfoil-lined rooms marked “PRIVATE.” Last time, in the Season 6 premiere, he tried to suggest that Hawaii was a “stepping off point,” but his clients (correctly) read this as a suicidal void. In “To Have and to Hold,” Don’s pitch is another void, a tiny slogan suspended above a french fry terrain.

“It feels like half an ad,” complains Timmy, noting the absence of the word “ketchup.” Don counters that the emptiness of the ad is precisely what is wanted; it’s the inside of the consumer’s mind. “And if you can get into that space, your ad can run all day.” As always, Don shows that he has some real insight about psychology, about desire, about fantasy—but these insights are no longer part of the times. Timmy gets it, but the style is wrong. “I think I still want to see our bottle.”

Peggy’s pitch, by contrast, is not simply about giving them exactly what they want (the word ketchup, the image of the bottle), but about excess: the font (Futura) is huge, and in all caps. Even the bottle is bigger (family size), but it’s not big enough: “Imagine this, forty feet tall. In Times Square.”

Peggy’s pitch, by contrast, is not simply about giving them exactly what they want (the word ketchup, the image of the bottle), but about excess: the font (Futura) is huge, and in all caps. Even the bottle is bigger (family size), but it’s not big enough: “Imagine this, forty feet tall. In Times Square.” When Megan talks about their invitation to have group sex with Mel and Arlene, she’s not so much shocked by the idea as she is by the style of presentation: “They were so out in the open,” marvels Megan. “It was a good strategy,” replies Don.