[The fourth in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 6 of AMC's Mad Men, posted in collaboration with the publication ofMADMEN, MADWORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, andthe 1960s(Duke University Press, March 2013) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

[The fourth in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 6 of AMC's Mad Men, posted in collaboration with the publication ofMADMEN, MADWORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, andthe 1960s(Duke University Press, March 2013) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]"A Tense Experiment"

Written by: Dana Polan (New York University)

I keep thinking about some of the narrative curiosities of this season's two-part opener for Mad Men: an initial shot (a man seeming to pump at the body of someone off-screen while a woman screams) that only makes sense as we move later into the narrative (he, it transpires, was Arnold, a doctor who luckily came into the lobby with his wife Sylvia just after the doorman had collapsed in Don and Megan's presence and who was able to perform successful C.P.R.), but then final moments that make us realize that what we were seeing earlier has now, again, to be rethought in light of very consequential new information (it turns out that Don's been having an affair with Sylvia—although we're never sure when that started).

|

| The Sixth Sense (1999) |

In like fashion, at the end of "The Doorway," we might wonder if Don and Sylvia ever exchanged meaningful glances that we missed the first time around, if there were any hints here or there of what we would later realize had already been going on some time earlier.

In like fashion, at the end of "The Doorway," we might wonder if Don and Sylvia ever exchanged meaningful glances that we missed the first time around, if there were any hints here or there of what we would later realize had already been going on some time earlier.Such works as these set up a tension then between the present-tense in which we watch them and a future that can challenge what we've been (already) seeing and turn it into a past-tense that we then have to rethink. We watch Don, Megan, the doctor and his wife a first time around but then later realize that whatever we thought we were watching needs revision.

|

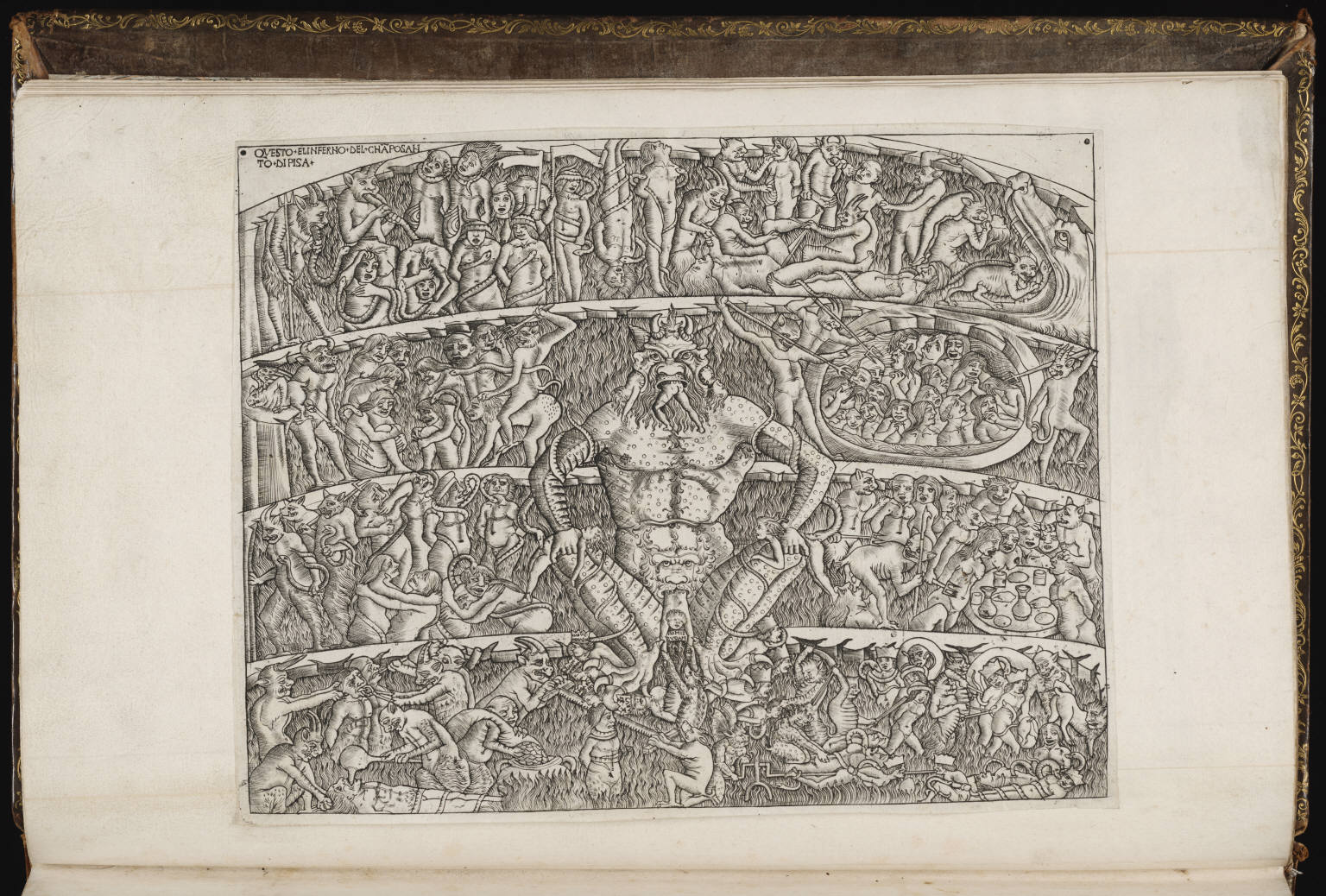

| Sandro Botticelli's illustration for Dante's Inferno (1481) |

Hence, then, an experiment in tense: I am not writing this blog after my assigned episode ends but while it unfolds (ok, to be honest, I'm doing it during the commercial breaks so there is still a degree of belatedness from the episode segments proper to commercials that follow on each segment). I want to write about what I know--or what I think I know --as the episode progresses and reflect on how that ongoing process of knowing went (that last, judgmental part will be written after). To be sure, I have some background from previous episodes to go on (but how helpful is that going to be in a series that often jumps to new situations and constantly revises acquired knowledge?), and I have a title for the episode to go on ("The Flood?" but, really, how useful is that?). I will watch and form hypotheses in the present, and then write them up on the fly as close as I can to the present-tense viewing. Here goes.

"It sounds very old world," declares one of the characters (Michael, a young Jewish copywriter) in "The Flood," referring to a blind date his father has set up for him even as he (the reluctant dater) boldly speaks to the woman he is out for the evening with in a way that signals his desire to move beyond the strictures and structures of the past into new territory (here, new sexual territory).

"It sounds very old world," declares one of the characters (Michael, a young Jewish copywriter) in "The Flood," referring to a blind date his father has set up for him even as he (the reluctant dater) boldly speaks to the woman he is out for the evening with in a way that signals his desire to move beyond the strictures and structures of the past into new territory (here, new sexual territory).  There's a lot of reference to pasts (for example, all the accounts the ad agencies, both Don's and Peggy's, used to have) but there's also a lot of suggestion that new worlds are being put into place (the episode opens, of course, with Peggy looking at a new apartment as her real estate agent tries to come to grips with new relations between the men and women she is arranging home or apartment ownership for). And, indeed, from its first segment on, "The Flood" seems in a way that at first develops gradually and then comes with the veritable force of a gunshot to be about conflicts of tense--the tensions between a pastness that still weighs the characters down and a fateful futurity that they are not fully equipped to deal with in all its ramifications.

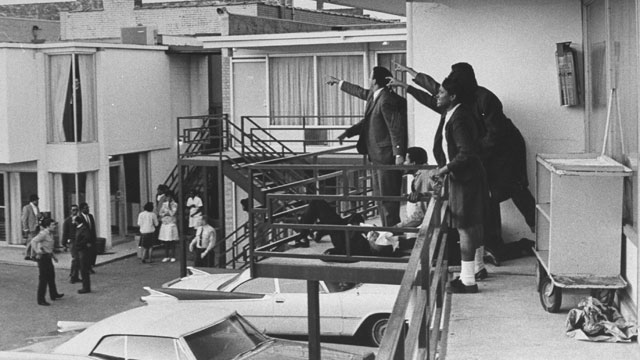

There's a lot of reference to pasts (for example, all the accounts the ad agencies, both Don's and Peggy's, used to have) but there's also a lot of suggestion that new worlds are being put into place (the episode opens, of course, with Peggy looking at a new apartment as her real estate agent tries to come to grips with new relations between the men and women she is arranging home or apartment ownership for). And, indeed, from its first segment on, "The Flood" seems in a way that at first develops gradually and then comes with the veritable force of a gunshot to be about conflicts of tense--the tensions between a pastness that still weighs the characters down and a fateful futurity that they are not fully equipped to deal with in all its ramifications. Historicity always has been hovering in the background of Mad Men--particularly so in this season where we hear references to real-world events (the war in Viet Nam, for instance) as muted reports that come from televisions somewhere offscreen (and sometimes are talked over by characters in the foreground). But with "The Flood," with the death of Martin Luther King, history floods in, and every character has to come to grips in whatever way with absolutely new conditions. We watch as characters fumble and one by one reveal their best or their worst. Think, for instance, of those supposedly empathetic hugs by whites with African Americans--hugs that are more than awkward (especially since they are supposed to be about denying racism but need to turn each African American woman into a symbol or direct token of her race).

Historicity always has been hovering in the background of Mad Men--particularly so in this season where we hear references to real-world events (the war in Viet Nam, for instance) as muted reports that come from televisions somewhere offscreen (and sometimes are talked over by characters in the foreground). But with "The Flood," with the death of Martin Luther King, history floods in, and every character has to come to grips in whatever way with absolutely new conditions. We watch as characters fumble and one by one reveal their best or their worst. Think, for instance, of those supposedly empathetic hugs by whites with African Americans--hugs that are more than awkward (especially since they are supposed to be about denying racism but need to turn each African American woman into a symbol or direct token of her race).  Or think of those endless machinations by this or that character to benefit from the tragedy in absolutely self-aggrandizing ways: for instance, Henry dreaming (with Betty) of a new political career or Peggy hoping (or being convinced by her real estate agent to hope) that new urban unrest will bring down the price of the apartment she wishes to buy. Mad Men is not merely a show that is watched in the present tense, like any other series, but it is also particularly and pointedly one in which the characters live in a present that often about self-interest and moment-to-moment improvisation to secure that self interest. This is not always a series about the larger picture or the longer view or the higher moral ground. (Ironically, though, we find that the characters we might have expected the worst from in such cases defeating our expectations: who might have imagined that Pete Campbell, for whatever reasons, would be the one to condemn profiteering from King's death?)

Or think of those endless machinations by this or that character to benefit from the tragedy in absolutely self-aggrandizing ways: for instance, Henry dreaming (with Betty) of a new political career or Peggy hoping (or being convinced by her real estate agent to hope) that new urban unrest will bring down the price of the apartment she wishes to buy. Mad Men is not merely a show that is watched in the present tense, like any other series, but it is also particularly and pointedly one in which the characters live in a present that often about self-interest and moment-to-moment improvisation to secure that self interest. This is not always a series about the larger picture or the longer view or the higher moral ground. (Ironically, though, we find that the characters we might have expected the worst from in such cases defeating our expectations: who might have imagined that Pete Campbell, for whatever reasons, would be the one to condemn profiteering from King's death?)  As we watch Mad Men in the present, across its seasons, we can have the sense that everything is being worked out at the moment, both by the characters--who often have to improvise to get by in the moment (often the great improviser, Don stumbles at this when early in "The Flood," he is taken aback by Sylvia's departure with Arnold for a weekend away and, losing his cool, flubs his lines)--and by the show itself which comes to us in bits and pieces that seem to hold out larger, significant resonances even as they slip away from us. At the same time, it's tempting to feel that there is a larger design to these fragments and to imagine there's a greater plan to the series: as we watch, we try to tap into the narrative design of the show and piece it all together (the "Next on Mad Men" previews are particularly adept at this fleeting promise of something more: there are seductive glimpses of a sense that flits away even as we cling to this or that fragment for deeper significance).

As we watch Mad Men in the present, across its seasons, we can have the sense that everything is being worked out at the moment, both by the characters--who often have to improvise to get by in the moment (often the great improviser, Don stumbles at this when early in "The Flood," he is taken aback by Sylvia's departure with Arnold for a weekend away and, losing his cool, flubs his lines)--and by the show itself which comes to us in bits and pieces that seem to hold out larger, significant resonances even as they slip away from us. At the same time, it's tempting to feel that there is a larger design to these fragments and to imagine there's a greater plan to the series: as we watch, we try to tap into the narrative design of the show and piece it all together (the "Next on Mad Men" previews are particularly adept at this fleeting promise of something more: there are seductive glimpses of a sense that flits away even as we cling to this or that fragment for deeper significance). But if the characters are now confronting the momentous nature of a history they often have ignored (and sometimes continue to ignore, as when Betty tries to get her children to stop watching the breaking news on television), there is little suggestion that the characters of Mad Men necessarily will themselves evolve in consequential fashion. "The heavens are telling us to change" announces one character (Randall, an insurance executive who's come to Don's firm seemingly to throw business its way), but he's presented as a veritable nut case whose interpretation of the calamities of the moment are laughable to both characters in the show (Stan can't resist the stoner's chortle at the absurdity of it all) and to we spectators. Mad Men is a series that cannot acknowledge intentional agency in the service of consequential change as anything more than foolish (as Megan tells Don, he doesn't, in contrast to her sanctimoniously radical father, need Karl Marx because he's got booze: dreams of revolutionary upheaval and escapist inebriation all amount to the same thing).

But if the characters are now confronting the momentous nature of a history they often have ignored (and sometimes continue to ignore, as when Betty tries to get her children to stop watching the breaking news on television), there is little suggestion that the characters of Mad Men necessarily will themselves evolve in consequential fashion. "The heavens are telling us to change" announces one character (Randall, an insurance executive who's come to Don's firm seemingly to throw business its way), but he's presented as a veritable nut case whose interpretation of the calamities of the moment are laughable to both characters in the show (Stan can't resist the stoner's chortle at the absurdity of it all) and to we spectators. Mad Men is a series that cannot acknowledge intentional agency in the service of consequential change as anything more than foolish (as Megan tells Don, he doesn't, in contrast to her sanctimoniously radical father, need Karl Marx because he's got booze: dreams of revolutionary upheaval and escapist inebriation all amount to the same thing).  Maybe, one might hope, there could indeed be meaningful change: towards the end of "The Flood," Don seems to have an epiphany that is precisely about the ways in which improvised, feigned performances of sentiment can turn into the real thing: seeing his son Bobby talk at the movies of sadness to a black janitor makes Don realize the pretending at fatherhood he's been acting at can turn into actual, even profound paternal feeling. But it as likely that none of this conversion to heartfelt sentiment will hold: not merely do characters in the show, Don especially, frequently forget their epiphanies and backslide into the very behavioral patterns they had promised to go beyond, but forgetfulness is also endemic to Mad Men itself as serial television, caught as it is between a progressive building up of knowledge and a scene to scene, episode to episode fragmentation that works for the moment but has no lasting power.

Maybe, one might hope, there could indeed be meaningful change: towards the end of "The Flood," Don seems to have an epiphany that is precisely about the ways in which improvised, feigned performances of sentiment can turn into the real thing: seeing his son Bobby talk at the movies of sadness to a black janitor makes Don realize the pretending at fatherhood he's been acting at can turn into actual, even profound paternal feeling. But it as likely that none of this conversion to heartfelt sentiment will hold: not merely do characters in the show, Don especially, frequently forget their epiphanies and backslide into the very behavioral patterns they had promised to go beyond, but forgetfulness is also endemic to Mad Men itself as serial television, caught as it is between a progressive building up of knowledge and a scene to scene, episode to episode fragmentation that works for the moment but has no lasting power. |

| Planet of the Apes (1968) |

|

| April 4, 1968 |

One constant debate about Mad Men has had to do with the seeming ways in which it sets up perhaps a gap between the limited perspective of its characters, rooted in their moment of the late 1950s into the 1960s (didn't they know, for instance, that all that cigarette smoking was bad for one's health!), and our superior knowledge from the enlightened 2000s. But the unfolding presentness of Mad Men as we watch it moment to moment closes that gap and makes us into improvisers, too--searching for a sense of an ending that is not yet here and that we're not yet sure will ever come.