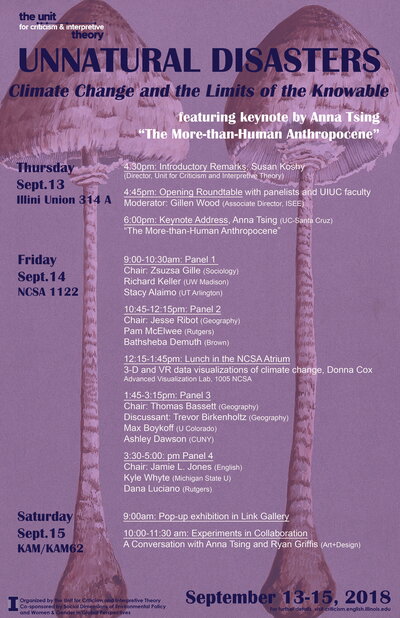

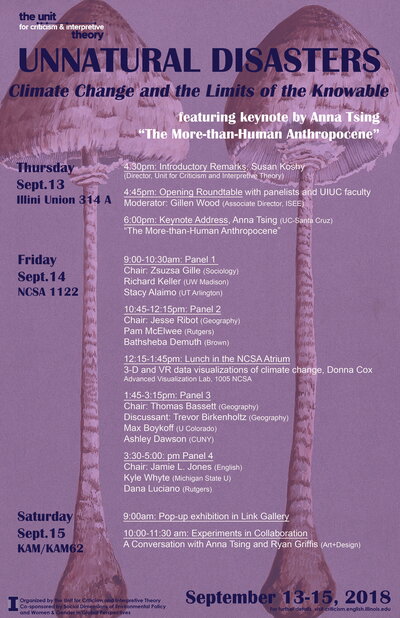

Organizing Committee

- Thomas Bassett (Geography & GIS)

- Trevor Birkenholtz (Geography & GIS)

- Jamie Jones (English)

- Susan Koshy (English/Asian American Studies)

- Jesse Ribot (Geography & GIS)

- Emanuel Rota (FRIT/History)

- Gillen Wood (English/ISEE)

- Zsuzsa Gille (Sociology)

Unnatural Disasters Conference Paper Abstracts

Stacy Alaimo (UT Arlington, English), “Divergent, Imperceptible, Unthinkable: Making Ocean Acidification Sensible”

Although it has been dubbed climate change’s “evil twin,” ocean acidification seems rather reserved and elusive for an unnatural disaster. Ocean acidification, which involves a slight shift in the Ph of the ocean’s waters, is intangible, even imperceptible, without scientific instruments, and yet unthinkable in terms of the enormity and strange divergence of its predicted effects. Science, environmental groups, and artists struggle to capture multiple phenomena resulting from acidification, resulting in a vertiginous yet urgent sense that reckoning with multispecies life in the anthropocene seas is an onto-epistemological pursuit that is as political as it is impossible.

Richard C. Keller (UW-Madison, History), “Perfect Storms: Extreme Heat and Social Vulnerability in a Volatile Climate”

The European heat wave of 2003 was perhaps the first event to generate global awareness of the threat of extreme heat in a changing climate. While the devastating mortality of 2003 led to the implementation of major heat response plans in much of western and central Europe, extreme heat remains an overwhelming threat on the continent and beyond. This paper explores the emerging threat of extreme heat in the twenty-first century, with particular attention to the divergent effects of heat in different climates. Through glimpses extreme heat events in Russia, South Asia, the American Southwest, East Asia, and western Europe, it points to the place-based intersection of social vulnerability and heat stress in a rapidly warming global climate.

Pam McElwee (Rutgers, Human Ecology), “Climate Change Adaptation as Environmental Rule in Southeast Asia”

In my recent book, Forests are Gold: Trees, People and Environmental Rule in Vietnam (2016) I argued for the concept of “environmental rule”, which occurs when states, organizations, or individuals use environmental or ecological reasons as justification for what is really a concern with social planning, and thereby intervene in such disparate areas as land ownership, population settlement, or cultural identities. Imposing a vision on landscapes has always been a role of the state, but what is unique about environmental rule is that while the justification for intervention is to “improve” or “protect” the environment itself, in reality, underlying improvements to people or society are envisioned. In this talk, I extend the analysis of environmental rule to climate change vulnerability and adaptation. Are some states in Southeast Asia using the concept of “climate change” to intervene in areas of life they have long wanted to change? Using examples from a database of adaptation actions in Vietnam, as well as similar examples from Burma and Indonesia, I will argue that climate change can be used as an excuse for states to do what they have long wanted to do: resettle ‘unruly’ peoples into more easily monitored zones, grant access to financially important landscapes to political allies, or ‘modernize’ culturally marginalized groups. I will discuss what the implications of this are, and the potential of adaptation actions to transform existing social orders.

Bathsheba Demuth, (Brown, History), “What is a Whale: Economics, Entropy, and Cosmologies of the Nonhuman”

Whales have been hunted by three distinct groups of hunters in the Bering Sea over the past two centuries: indigenous Yupik and Inupiaq whalers, capitalist commercial whalers, and communist industrial whalers. I examine how ideas of what a whale is and how it should be valued came to be understood through the labor of their killing. The labor of hunting whales illuminates how three different cosmologies of production understood work, pain, and death both human and otherwise. This talk examines what lessons we might draw from whaling in addressing the challenges of living with non-human beings in a changing climate.

Max Boykoff (U of Colorado), “A Laughing Matter? Moving from Scientific Ways of Knowing to Confrontations with Climate Change through Humor”[1]

Why fuse climate change and comedy? Anthropogenic climate change is one of the most prominent and existential challenges of the 21st century. Consequently, public discourses typically consider climate change as ‘threat’ with doom, gloom and psychological duress sprinkled throughout. Humor and comedy have been increasingly mobilized as culturally resonant vehicles for effective climate change communications, as everyday forms of resistance and tools of social movements, while providing some levity along the way. Yet, critical assessments see comedy as a distraction from the serious nature of climate change problems. Primarily through Michel Foucault’s conception of biopower and through Ben Anderson’s approaches to affect, this presentation will interrogate how comedy and humor potentially exert power to impact new ways of thinking/acting about anthropogenic climate change. More widely, this presentation will critically examine ways in which experiential, emotional, and aesthetic learning can inform scientific ways of knowing. These dynamics will be explored through the ‘Stand Up for Climate Change’ initiative through the ‘Inside the Greenhouse’ project where efficacy of humor in climate change communication is considered while individuals and groups also build tools of communication through humor. This is a multi-modal experiment in sketch comedy, stand-up and improvisation involving undergraduate students, culminating in a set of performances. In addition, the project ran an international video competition. Through this case, I interrogate how progress can be made along key themes of awareness, efficacy, feeling/emotion/affect, engagement/problem solving, learning and new knowledge formation, even though many challenges still remain. While science is often privileged as the dominant way by which climate change is articulated, comedic approaches can influence how meanings course through the veins of our social body, shaping our coping and survival practices in contemporary life. However, this is not a given. By tapping into these complementary ways of knowing, ongoing challenges remain regarding how researcher, scholars, communicators and everyday citizens can more effectively develop strategies to ‘meet people where they are’ through creative climate communications.

[1] This is based on research that I have undertaken with Beth Osnes from the Department of Theatre and Dance at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Ashley Dawson (CUNY, English), “Hope in an Era of Climate Crisis: Rapid Adaptation and Mitigation Planning”

We are losing. Losing beloved people and places to anthropogenic climate disasters, and losing hope that global elites will take the action urgently needed to mitigate carbon emissions. Cities need to adapt to increasingly destructive heat waves, droughts, hurricanes, and other “natural” disasters. Adaptations of various sorts will happen – indeed, they are already unfolding in fits and starts. The danger is that these steps to adapt to climate chaos will intensify the already appalling inequalities that characterize the world’s extreme cities. For the global climate justice movement, it is imperative to imagine alternatives to the dystopian urban present. How might climate adaptation be conceived of as an opportunity to heal the suppurating wounds of the extreme city rather than to widen these gashes? How can we frame (and implement) redemptive urban imaginaries in order to shore up social solidarity and heal the divisions that imperil urban sustainability? This presentation explores a number of cutting-edge Climate Action Plans that, I argue, provide increasingly essential tools to envision an equitable urban future during an age of climate chaos.

Kyle Powys Whyte (Michigan State U, Philosophy and Community Sustainability), “Indigenous Dystopias, Colonial Fantasies: Justice, Reconciliation and the Climate Change Crisis”

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s effort to block the Dakota Access Pipeline is among the most recent Indigenous-led movements connected to climate justice. Indigenous efforts have ranged from direct confrontations against extractive industries to policy work at international and national levels to knowledge networks seeking to reform climate science to innovations at the level of local practical planning processes designed to use traditional knowledge systems as strategies for adaptation and vulnerability assessment. Reflecting on these movements, Indigenous peoples are contributing to how people understand climate justice. In particular, Indigenous peoples are shaping theories about the relationship between colonialism and human fantasies about or dread of future scenarios, offering broader conceptions of the value of Indigenous knowledges for supporting resilience, and expressing visions of the future that displace Eurocentric notions, especially ‘the Anthropocene’. Indigenous climate justice movements are about achieving political reconciliation with colonial states in ways that are rarely discussed in other climate justice discourses.

Dana Luciano (Rutgers), “Apocalypse: The View from Here”

What does it mean to look back on the end of the world? The trope, familiar from the burgeoning genre of cli-fi, is generally employed as imaginative correlative to the practice of invoking climate change as an impending apocalyptic threat. The wreckage revealed in the backward glance, it is hoped, will intensify the desire not to have seen it, bringing about the kind of change needed to prevent the imminent devastation. But such hopes are complicated by the partiality of the retrospective view. As Kyle Powys Whyte observes, for instance, positioning environmental dread as the affective keynote of the political present risks privileging the settler subject as the “proper” subject of climate change, in contrast to “some indigenous subjects [who] already inhabit what our ancestors would privilege as a dystopian future.”[2]

My talk pursues the question of post-apocalyptic survival from a different perspective: specifically, that of queer settler subjects living in the wake of the devastation wrought by the first decades of the AIDS pandemic. Following Sarah Ensor’s contention that queer writing about AIDS offers an unexpected resource to environmental thinkers and activists, I reflect on the 1993 AIDS documentary Silverlake Life: The View from Here (Tom Joslin/Peter Friedman), a film that, on its surface, has nothing to do with climate change.[3] Looking back at the film’s depiction of the crisis ordinary of two white gay men living with advanced HIV disease, I explore its powerful imbrication of living and dying, resignation and optimism, and repulsion and love as guides to a more politically nuanced, ethically capacious understanding of environmental affect.

[2] Kyle Powys Whyte, “Our Ancestors’ Dystopia Now: Indigenous Conservation and the Anthropocene,” in Ursula K. Heise et. al., eds, The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities (Routledge, 2017).

[3] Sarah Ensor, “Terminal Regions: Queer Ecocriticism at the End,” in Alastair Hunt and Stephanie Youngblood, eds., Against Life (Northwestern University Press, 2016).